King of Rome

| King of Rome | |

|---|---|

| Former Monarchy | |

|

|

| Capitoline Wolf | |

|

|

| Lucius Tarquinius Superbus | |

| First monarch | Romulus |

| Last monarch | Lucius Tarquinius Superbus |

| Official residence | Rome |

| Monarchy started | 753 BC |

| Monarchy ended | 509 BC |

| Ancient Rome | ||||

This article is part of the series: |

||||

|

|

||||

| Periods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Kingdom 753 BC – 509 BC Roman Republic

|

||||

| Roman Constitution | ||||

|

Constitution of the Kingdom |

||||

| Ordinary Magistrates | ||||

|

||||

| Extraordinary Magistrates | ||||

|

||||

| Titles and Honours | ||||

Emperor

|

||||

| Precedent and Law | ||||

|

||||

|

Other countries · Atlas |

The King of Rome (Latin: rex, regis) was the chief magistrate of the Roman Kingdom.[1] According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 BC upon the Palatine Hill. Seven legendary kings are said to have ruled Rome until 509 BC, when the the last king was overthrown. These kings ruled for an average of 35 years. Since Rome's records were destroyed in 390 BC when the city was sacked, it is impossible to know for certian how many kings actually ruled the city, or if any of the deeds atributed to the individual kings, by later writers, are accurate.

The kings after Romulus were not known to be dynasts and no reference is made to the hereditary principle until after the fifth king Tarquinius Priscus. Consequently, some have assumed that the Tarquins and their attempt to institute a hereditary monarchy over this conjectured earlier elective monarchy resulted in the formation of the republic.

Contents |

Overview

Early Rome was not self-governing, and was ruled by the king (Rex), sometimes from a nearby Etruscan city-state. The king possessed absolute power over the people. The Senate was a weak oligarchy, capable of exercising only minor administrative powers, so that Rome was ruled by an Etruscan absolute monarchy. While Rome herself had a Senate, its main function was to carry out and administer the wishes of the King.

The insignia of the king was twelve lictors wielding the fasces, a throne of a Curule chair, the purple Toga Picta, red shoes, and a white diadem around the head. Only the king could wear a purple toga.

The supreme power of the state was vested in the Rex, whose position made him the:

| Title | Description |

|---|---|

| Head of State | served as the chief representative of Rome in its relations with foreign powers and received all foreign ambassadors. |

| Head of Government | served as the chief executive with the power to enforce the laws, managed all state owned property, disposed of conquered territory, and oversaw all public works. |

| Commander in Chief | commander of the Roman military with the sole power to levy and organize the legions, to appoint military leaders, and to conduct war. |

| Chief Priest | served as official representative of Rome and her people before the Roman gods with the power of general administrative control over the Roman religion. |

| Chief Legislator | formulated and proposed legislative proposals as he deemed necessary. |

| Chief Judge | adjudicated all civil and criminal cases. |

Chief Priest

What is known for certain is that the king alone possessed the right to the auspice on behalf of Rome as its chief augur, and no public business could be performed without the will of the gods made known through auspices. The people knew the king as a mediator between them and the gods (cf. Latin pontifex "bridge-builder", in this sense, between man and the gods) and thus viewed the king with religious awe. This made the king the head of the national religion and its chief executive. Having the power to control the Roman calendar, he conducted all religious ceremonies and appointed lower religious offices and officers. It was Romulus who instituted the augurs and who was believed to have been the best augur of all. Likewise, King Numa Pompilius instituted the pontiffs and through them developed the foundations of the religious dogma of Rome.

Chief Executive

Beyond his religious authority, the king was invested with the supreme military, executive, and judicial authority through the use of imperium. The imperium of the king was held for life and protected him from ever being brought to trial for his actions. As being the sole owner of imperium in Rome at the time, the king possessed ultimate executive power and unchecked military authority as the commander-in-chief of all Rome's legions. His executive power and his sole imperium allowed him to issue decrees with the force of law. Also, the laws that kept citizens safe from the misuse of magistrates owning imperium did not exist during the times of the king.

Another power of the king was the power to either appoint or nominate all officials to offices. The king would appoint a tribunus celerum to serve as both the tribune of Ramnes tribe in Rome but also as the commander of the king's personal bodyguard, the Celeres. The king was required to appoint the tribune upon entering office and the tribune left office upon the king's death. The tribune was second in rank to the king and also possessed the power to convene the Curiate Assembly and lay legislation before it.

Another officer appointed by the king was the praefectus urbi, which acted as the warden of the city. When the king was absent from the city, the prefect held all of the king's powers and abilities, even to the point of being bestowed with imperium while inside the city. The king even received the right to be the sole person to appoint patricians to the Senate.

Chief Judge

The king's imperium granted him both military powers as well as qualified him to pronounce legal judgment in all cases as the chief justice of Rome. Though he could assign pontiffs to act as minor judges in some cases, he had supreme authority in all cases brought before him, both civil and criminal. This made the king supreme in times of both war and peace. While some writers believed there was no appeal from the king's decisions, others believed that a proposal for appeal could be brought before the king by any patrician during a meeting of the Curiate Assembly.

To assist the king, A council advised the king during all trials, but this council had no power to control the king's decisions. Also, two criminal detectives (Quaestores Parridici) were appointed by him as well as a two man criminal court (Duumviri Perduellionis) which oversaw for cases of treason.

Chief Legislator

Under the kings, the Senate and Curiate Assembly had very little power and authority; they were not independent bodies in that they possessed the right to meet together and discuss questions of state. They could only be called together by the king and could only discuss the matters the king laid before them. While the Curiate Assembly did have the power to pass laws that had been submitted by the king, the Senate was effectively an honorable council. It could advise the king on his action but by no means could prevent him from acting. The only thing that the king could not do without the approval of the Senate and Curiate Assembly was to declare war against a foreign nation. These issues effectively allowed the King to more or less rule by decree with the exception of the above mentioned affairs.

Election

Whenever a king died, Rome entered a period of interregnum. Supreme power of the state would devolve to the Senate, which was responsible for finding a new king. The Senate would assemble and appoint one of its own members the interrex to serve for a period of five days with the sole purpose of nominating the next king of Rome. After the five day period, the interrex would appoint (with the Senate's consent) another Senator for another five day term. This process would continue until a new king was elected. Once the interrex found a suitable nominee to the kingship, he would bring the nominee before the Senate and the Senate would review him. If the Senate passed the nominee, the interrex would convene the Curiate Assembly and presided as its president during the election of the King.

Once proposed to the Curiate Assembly, the people of Rome could either accept or reject him. If accepted, the king-elect did not immediately enter office. Two other acts had still to take place before he was invested with the full regal authority and power. First it was necessary to obtain the divine will of the gods respecting his appointment by means of the auspices, since the king would serve as high priest of Rome. This ceremony was performed by an augur, who conducted the king-elect to the citadel where he was placed on a stone seat as the people waited below. If found worthy of the kingship, the augur announced that the gods had given favorable tokens, thus confirming the king’s priestly character.

The second act which had to be performed was the conferring of the imperium upon the King. The Curiate Assembly’s previous vote only determined who was to be king, and had not by that act bestowed the necessary power of the king upon him. Accordingly, the king himself proposed to the Curiate Assembly a law granting him imperium, and the Curiate Assembly by voting in favor of the law would grant it.

In theory, the people of Rome elected their leader, but the Senate had most of the control over the process.

Kings of Rome (753 BC-509 BC)

| Portrait | Name | King From | King Until | Succession |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Romulus REX ROMVLVVS |

753 BC | 716 BC | |

|

Numa Pompilius REX NVMA POMPILIVS |

715 BC | 674 BC | |

|

Tullus Hostilius REX TVLLVS HOSTILIVS |

673 BC | 642 BC | |

|

Ancus Marcius REX ANCVS MARCIVS |

641 BC | 617 BC | |

|

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus REX LVCIVS TARQUINIVS PRISCVS |

616 BC | 579 BC | |

|

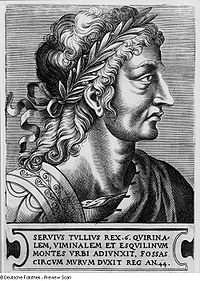

Servius Tullius REX SERVIVS TVLLIVS |

578 BC | 535 BC | |

|

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus REX LVCIVS TARQVINIVS SVPERBVS |

534 BC | 509 BC |

Titus Tatius, king of the Sabines, was also joint king of Rome with Romulus for five years, until his death. However he is not traditionally counted among the seven kings of Rome.

Notes

- ↑ Outline of Roman History William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, Cincinnati, Chicago: American Book Company (1901)

External links

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||